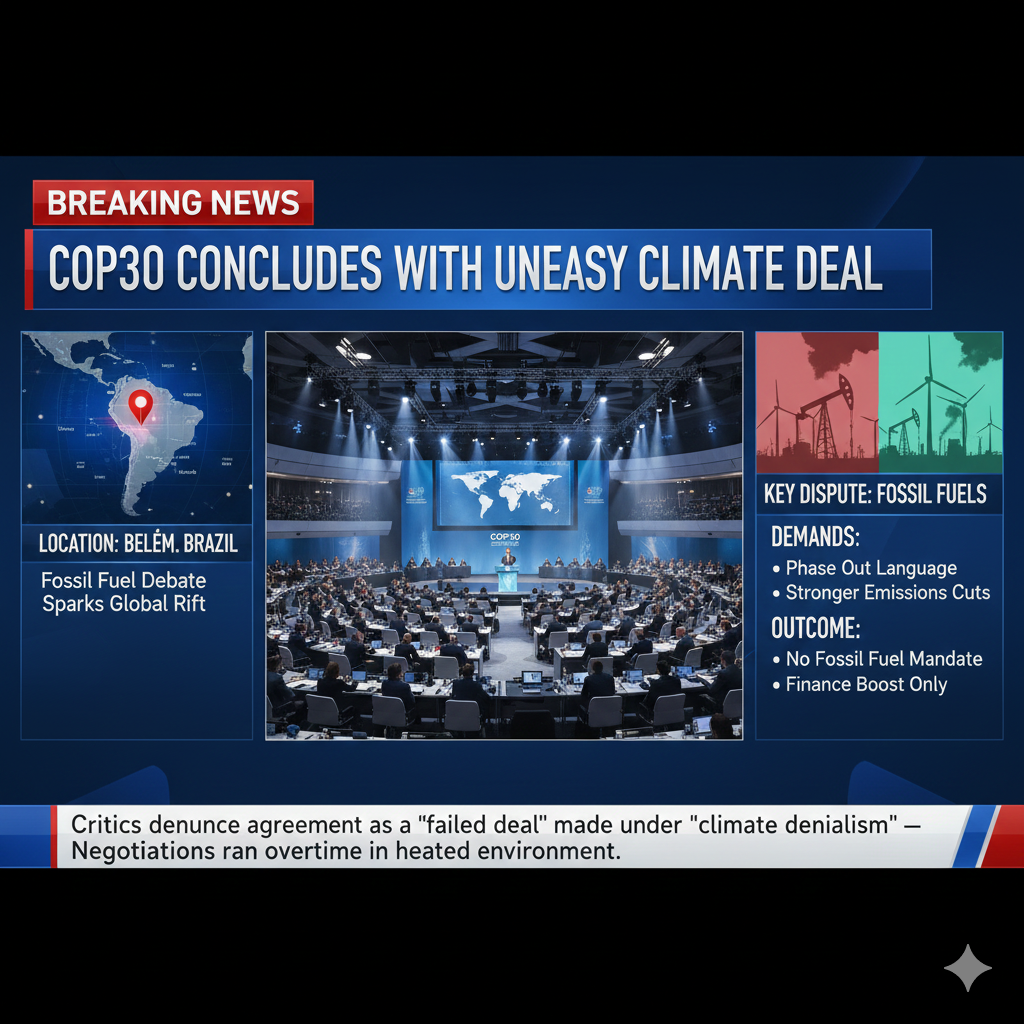

BELÉM, BRAZIL — The United Nations climate summit, COP30, has descended into a high-stakes diplomatic standoff in the heart of the Amazon, threatening to unravel years of incremental progress on climate action.

As the two-week conference nears its scheduled conclusion, deep geopolitical fractures have been exposed by a controversial move from the host nation. In the pre-dawn hours of Friday, the Brazilian presidency released a draft text for the final agreement that notably—and shockingly to many delegates—stripped out all references to a coordinated global plan to shift away from oil, gas, and coal.

The omission has triggered a revolt among a coalition of more than 30 nations, who have arguably drawn a line in the sand: they will not sign a deal that lacks a clear commitment to a fossil fuel roadmap. With the clock ticking toward the official 6 p.m. deadline, the summit is poised for a dramatic, and potentially acrimonious, overtime showdown.

The “Zero Draft” Shockwave

The release of draft texts at UN climate summits is usually a moment of high tension, but Friday’s document, known in diplomatic circles as a “draft decision,” landed with the weight of a sledgehammer.

Previous iterations of the text had included a “range of options” regarding the future of fossil fuels. These options allowed negotiators to debate the strength of the language—ranging from a “rapid phaseout” to a more gradual “transition.” However, the document released by the Brazilian presidency removed these options entirely. Instead of choosing a lane, the text simply removed the road.

For climate advocates and the “High Ambition Coalition”—a bloc of nations pushing for aggressive climate targets—the silence of the text was deafening. The burning of fossil fuels is unequivocally the primary driver of anthropogenic global warming. To produce a climate agreement in 2025 that fails to mention the root cause of the crisis is seen by many delegations not just as a failure, but as a regression.

EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra did not mince words in his assessment of the document. “We are disappointed with the text currently on the table,” Hoekstra said in a statement issued shortly after the draft circulated. He emphasized that the document “lacked ambition” and failed to provide the necessary signals to markets and governments that the era of fossil fuels is drawing to a close.

The Revolt of the 30: “No Roadmap, No Deal”

The backlash was immediate and organized. Late Thursday, anticipating the weakness of the incoming text, a group of more than 30 nations sent a preemptive letter to the COP30 presidency. The signatories included a diverse array of economies and vulnerabilities, ranging from European powerhouses like France, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands, to climate-vulnerable nations such as Kenya, the Marshall Islands, and Colombia.

Their message was blunt: The current draft does not meet the “minimum conditions required for a credible COP outcome.”

The letter explicitly stated, “We cannot support an outcome that does not include a roadmap for implementing a just, orderly, and equitable transition away from fossil fuels.”

This phrasing is critical. It refers back to the historic “UAE Consensus” reached at COP28 in Dubai two years ago. There, for the first time, nations agreed to “transition away” from fossil fuels. However, that agreement was criticized for lacking a “how.” The push at COP30 in Belém was supposed to be about turning that vague promise into a concrete “roadmap”—a timeline of action. By removing the concept of a roadmap entirely, the current draft effectively renders the Dubai promise toothless.

This coalition has effectively threatened to block the consensus. Under UN rules, the final agreement must be adopted by all nearly 200 participating governments. If this bloc of 30 holds firm, there will be no deal.

The Geopolitical Divide: Ambition vs. Resistance

The removal of the fossil fuel language is widely seen as a concession to a powerful bloc of oil-and-gas-producing nations, led most prominently by Saudi Arabia.

Throughout the two-week conference, negotiators have described a “wall of resistance” from the Arab Group and other petrostates. According to diplomatic sources, these nations have argued that the UN climate forum should focus strictly on emissions reduction (which allows for the continued use of oil and gas if carbon capture technology is used) rather than targeting the energy sources themselves.

Saudi Arabia and its allies have reportedly opposed any prescriptive language that dictates national energy policies, viewing a “roadmap” as an infringement on sovereignty and a threat to their economic survival.

However, the resistance is not purely coming from wealthy oil states. There is a complex dynamic involving the “Global South” and the G77 negotiating bloc. A negotiator from a developing country, speaking to Reuters, illuminated the nuance of the standoff. They noted that their government does not inherently oppose a phase-out. Instead, they are using the issue as leverage.

“You can’t keep saying that things that matter to us are no longer important and that things that matter to the developed countries are the only things that are important,” the negotiator explained.

For many developing nations, the priority is finance. They argue that they cannot be expected to sign up for a roadmap that disrupts their economic development unless wealthy nations—who burned fossil fuels for a century to get rich—put significantly more money on the table to pay for the transition. If the draft text offers little on finance (which this draft does), these nations see no reason to concede on fossil fuels.

Canada’s Careful Tightrope Walk

Notably absent from the letter signed by the UK, France, and Germany was Canada.

Despite branding itself as a climate leader and being a member of various progressive climate alliances, Canada did not sign the demand for a fossil fuel roadmap. This absence highlights the perpetual tension in Canadian climate policy: the country is a G7 climate advocate, but also the world’s fourth-largest oil producer.

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) confirmed on Friday that they were not signatories. In a carefully worded statement, an ECCC spokesperson said, “Canada remains fully committed to advancing global climate action and supporting a transition away from fossil fuels in ways that respect national priorities and circumstances.”

The statement added that Canada is focused on “practical” outcomes consistent with its domestic direction. This language—”national priorities and circumstances”—is often diplomatic code for refusing to commit to a binding international timeline that might conflict with the economic realities of a country’s resource sector. By staying off the letter, Canada avoids a direct diplomatic confrontation with its oil-producing allies while still verbally supporting the “transition.”

The Finance Gap: The Other Elephant in the Room

While the fossil fuel fight grabs the headlines, the draft text’s section on finance—or the lack thereof—is equally responsible for the gridlock.

The draft currently calls for global efforts to “triple the financing available” to help nations adapt to climate change by 2030, using 2025 levels as a baseline. On the surface, this sounds ambitious. However, the text is crucially vague on where this money will come from.

Developing nations have demanded legally binding commitments of public funds (grants and low-interest loans) from developed nations. The draft, however, does not specify that the money must come from wealthy government treasuries. It leaves the door open for the funding to come from “other sources,” such as the private sector or multilateral development banks.

For the Global South, relying on the private sector for “adaptation” finance is a non-starter. Private investors are happy to fund solar farms (which generate profit), but they rarely fund sea walls, flood drainage systems, or drought-resistant crops (which protect lives but generate no revenue). Without a guarantee of public finance, developing nations are refusing to agree to the stringent fossil fuel roadmaps demanded by the EU.

What Happens Next?

The conference is scheduled to end at 6 p.m. local time on Friday, but in the world of UN climate diplomacy, deadlines are merely suggestions. It is almost certain that negotiations will bleed into Saturday, and perhaps even Sunday.

The “public plenary” session, set to begin around 8 a.m. ET, will likely be a theater of frustration. Countries will take turns denouncing the text—some for being too weak on fossil fuels, others for being too weak on finance, and others for being too intrusive on sovereignty.

The Brazilian presidency now faces a herculean task. They must produce a new draft that bridges an almost unbridgeable gap. To save the summit, they likely need to:

-

Reintroduce language on fossil fuels that is strong enough to appease the EU and island nations, but vague enough to keep Saudi Arabia from walking out.

-

Beef up the financial commitments to bring the developing world on board.

If they fail, COP30 could end without a consensus agreement. In the context of a year that has seen record-breaking heat, floods, and fires, a “no deal” outcome in the Amazon would be a devastating signal to the world that multilateralism is failing to keep pace with the climate crisis.

For now, the text is blank on the most important issue facing humanity. The next 24 hours will determine if the world can fill in the blanks, or if the page will remain empty.